Merpeople are—and always have been—everywhere. From coffeehouses to tuna cans, church carvings to cave walls, cinema screens to cosplaying, sightings to scientific studies, humans have fostered an intimate, ever-evolving relationship with these hybrid creatures. In doing so, we repeatedly demonstrate a fascination with mermaids and mermen which extends well beyond simple fantasy or myth.

As my forthcoming book, Merpeople: A Human History (Reaktion Books) argues, humankind’s ongoing obsession with merpeople reveals much about our place in the world, and how we continuously use mermaids and tritons as a sort of mirror which reflects our own hopes, dreams, and desires. Merpeople is divided into six chapters (with 117 accompanying images) that chronologically trace humanity’s relationship with merpeople.

[asa2_img img=”1″ size=”LargeImage” width=”375″ height=”500″ align=”center” show_title=”no” show_button=”no”]1789143144[/asa2_img]Merpeople Chapter Reviews

Chapter One uncovers merpeople’s ancient roots, delving into Babylonian, Greek, and Roman depictions of mermaids and tritons. Amazingly, sculptures dating back to the eighth-century BCE show a merman accompanying the Assyrian king, Sargon II’s fleet of ships. By the medieval period, the Christian Church adopted these supposedly “pagan” depictions of merpeople into dangerous symbols of lust, greed, and sexuality. Hundreds of Western cathedrals now boast carvings, sculptures, and paintings of mermaids and mermen on and in their walls.

In Chapter Two, I demonstrate how, during the “Age of Discovery” (roughly 1500 to 1700), Westerners expected to find merpeople in New Worlds. And they did—dozens of reports of mermaid interactions surfaced during this period, and mapmakers regularly placed merpeople in the far oceans.

In Chapter Three, I trace this phenomenon into the erudite “Enlightenment” period of the eighteenth century, when Western philosophers began to debate the existence of merpeople. Some contended that they were real creatures, and even went so far as to draw realistic specimens and use long histories of sightings as proof of their existence. Others argued that no such thing could possibly exist. But, they were debating, and merpeople were gaining prominence in the minds of Westerners elite and common alike. In

Chapter Four, I show how Westerners’ belief in merpeople both peaked and crashed during the nineteenth century when an English ship captain named Eades purchased a supposed “mermaid” specimen from Japan in 1822. The shriveled little creature toured throughout England for a few years but was revealed to be a fake (a stitched together monkey and fish). In 1842, the American showman, P.T. Barnum purchased Eades’ mermaid and made a ton of money off of displaying it in America, before it was also revealed as a fake. This destroyed belief in merpeople, and by the end of the nineteenth century they were no more than myths and jokes.

As I show in Chapter Five, in the twentieth-century mermaids arose as stars of the cinema and advertising—the ultimate symbol of modern capitalism, so driven by sex, power, and profit. But merpeople’s popularity extended far beyond North America and Europe.

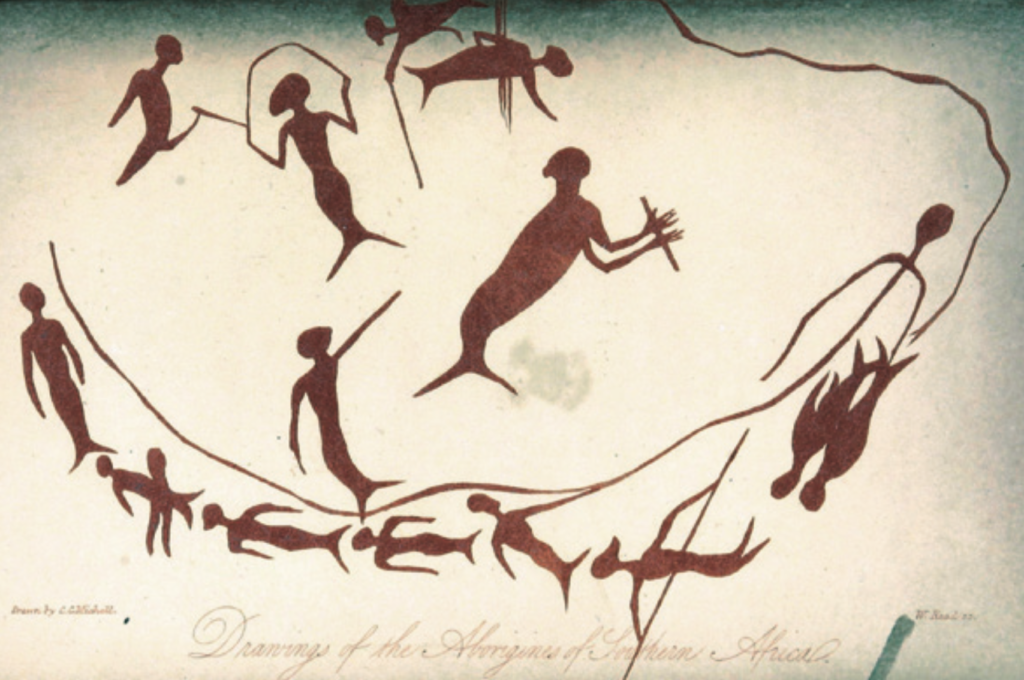

In Chapter Six, I follow mermaids and tritons throughout time and space to show how these creatures have been depicted by a vast array of societies around the globe. Ancient “bushmen” drew fishtailed creatures on cave walls in the South African desert and Middle Eastern sculptors carved twin-tailed mermen into arches. Incredibly, illustrations and stories of merpeople—whether in Japan, South America, Russia, Native North, and South America, West Africa, India, China, or Thailand—retained a shockingly similar form. How is this possible?

I think it’s best to end this post with a question, as our relationship with merpeople repeatedly raises far more questions than answers. Hopefully, in reading Merpeople: A Human History, you will be inspired to reflect upon your own relationship with these ancient hybrid creatures.

You can pre-order the book for $27.50 at the link. It releases in August.

[asa2_img img=”1″ size=”LargeImage” width=”375″ height=”500″ align=”center” show_title=”no” show_button=”no”]1789143144[/asa2_img]

Vaughn Scribner is an assistant professor of history at the University of Central Arkansas. He has published numerous articles on early American history and has written another book, Inn Civility: Urban Taverns and Early American Civil Society (New York: New York University Press, 2019). He lives in Conway, AR with his wife, Kristen, and their large tabby cat, “D.”

References for Images:

David Lewis-Williams, Thomas A. Dowson, and Janette Deacon, ‘Rock Art and Changing Perceptions of Southern Africa’s Past: Ezeljagdspoort Reviewed,’ Antiquity 67 (1993), pp. 273-291; Renée Rust and Jan Van Der Poll, Water, Stone, and Legend: Rock Art of the Klein Karoo (Cape Town, 2011), pp. 91-120; Thomas A. Dawson, ‘Reading Art, Writing History: Rock Art and Social Change in Southern Africa,’ World Archaeology 25:3 (1994), pp. 332-345; A.B. Smith, ‘Hunters and Herders in the Karoo Landscape,’ in The Karoo: Ecological Patterns and Processes, ed. W. Richard J. Dean and Suzanne J. Milton (Cambridge, UK, 2004), pp. 255

meadow

May 14, 2022theres a giant mermaid image that spans the entire west coast of the americas, she must be the lord of hosts from the holy bible. since the devil beside her is desintigrating. Its also reminescent of Isis and Osiris, with Osiris’s brother Set the dog biting and dismembering him, theres a ring on her finger and a six pointed star on her head.

Manifestation Mondays: Do You Have a Siren’s Calling? – Alchemic Seer

May 17, 2022[…] Merpeople: A Human History […]